11 Software Engineering

11.1 Mathematical model

Let \(u_t\), \(u_{tt}\), \(u_x\), \(u_{xx}\) denote derivatives of \(u\) with respect to the subscript, i.e., \(u_{tt}\) is a second-order time derivative and \(u_x\) is a first-order space derivative. The initial-boundary value problem implemented in the wave1D_dn_vc.py code is

\[ u_{tt} = (q(x)u_x)_x + f(x,t),\quad x\in (0,L),\ t\in (0,T] \] \[ u(x,0) = I(x),\quad x\in [0,L] \] \[ u_t(x,0) = V(t),\quad x\in [0,L] \] \[ u(0,t) = U_0(t)\text{ or } u_x(0,t)=0,\quad t\in (0,T] \] \[ u(L,t) = U_L(t)\text{ or } u_x(L,t)=0,\quad t\in (0,T] \tag{11.1}\] We allow variable wave velocity \(c^2(x)=q(x)\), and Dirichlet or homogeneous Neumann conditions at the boundaries.

11.2 Numerical discretization

The PDE is discretized by second-order finite differences in time and space, with arithmetic mean for the variable coefficient \[ [D_tD_t u = D_x\overline{q}^xD_x u + f]^n_i \tp \] The Neumann boundary conditions are discretized by \[ [D_{2x}u]^n_i=0, \] at a boundary point \(i\). The details of how the numerical scheme is worked out are described in Section 2.14 and Section 2.21.

11.3 A solver function

The software engineering patterns presented in this appendix (classes like Storage, Parameters, Problem, Mesh, Function, Solver) are implemented in src/softeng2/. Key files include:

src/softeng2/Storage.py- Data persistence with joblibsrc/softeng2/wave1D_oo.py- Object-oriented wave solver withParametersclasssrc/softeng2/wave2D_u0.py- 2D wave implementations

These serve as reference implementations for the patterns discussed.

The general initial-boundary value problem solved by finite difference methods. For modern implementations using Devito, see Section 2.12. This section covers software engineering principles that apply broadly to scientific computing.

11.4 Storing simulation data in files

Numerical simulations produce large arrays as results and the software needs to store these arrays on disk. Several methods are available in Python. We recommend to use tailored solutions for large arrays and not standard file storage tools such as pickle (cPickle for speed in Python version 2) and shelve, because the tailored solutions have been optimized for array data and are hence much faster than the standard tools.

11.5 Using savez to store arrays in files

11.5.1 Storing individual arrays

The numpy.storez function can store a set of arrays to a named file in a zip archive. An associated function numpy.load can be used to read the file later. Basically, we call numpy.storez(filename, **kwargs), where kwargs is a dictionary containing array names as keys and the corresponding array objects as values. Very often, the solution at a time point is given a natural name where the name of the variable and the time level counter are combined, e.g., u11 or v39. Suppose n is the time level counter and we have two solution arrays, u and v, that we want to save to a zip archive. The appropriate code is

import numpy as np

u_name = 'u%04d' % n # array name

v_name = 'v%04d' % n # array name

kwargs = {u_name: u, v_name: v} # keyword args for savez

fname = '.mydata%04d.dat' % n

np.savez(fname, **kwargs)

if n == 0: # store x once

np.savez('.mydata_x.dat', x=x)Since the name of the array must be given as a keyword argument to savez, and the name must be constructed as shown, it becomes a little tricky to do the call, but with a dictionary kwargs and **kwargs, which sends each key-value pair as individual keyword arguments, the task gets accomplished.

11.5.2 Merging zip archives

Each separate call to np.savez creates a new file (zip archive) with extension .npz. It is very convenient to collect all results in one archive instead. This can be done by merging all the individual .npz files into a single zip archive:

def merge_zip_archives(individual_archives, archive_name):

"""

Merge individual zip archives made with numpy.savez into

one archive with name archive_name.

The individual archives can be given as a list of names

or as a Unix wild chard filename expression for glob.glob.

The result of this function is that all the individual

archives are deleted and the new single archive made.

"""

import zipfile

archive = zipfile.ZipFile(

archive_name, 'w', zipfile.ZIP_DEFLATED,

allowZip64=True)

if isinstance(individual_archives, (list,tuple)):

filenames = individual_archives

elif isinstance(individual_archives, str):

filenames = glob.glob(individual_archives)

for filename in filenames:

f = zipfile.ZipFile(filename, 'r',

zipfile.ZIP_DEFLATED)

for name in f.namelist():

data = f.open(name, 'r')

archive.writestr(name[:-4], data.read())

f.close()

os.remove(filename)

archive.close()Here we remark that savez automatically adds the .npz extension to the names of the arrays we store. We do not want this extension in the final archive.

11.5.3 Reading arrays from zip archives

Archives created by savez or the merged archive we describe above with name of the form myarchive.npz, can be conveniently read by the numpy.load function:

import numpy as np

array_names = np.load(`myarchive.npz`)

for array_name in array_names:11.6 Using joblib to store arrays in files

The Python package joblib has nice functionality for efficient storage of arrays on disk. The following class applies this functionality so that one can save an array, or in fact any Python data structure (e.g., a dictionary of arrays), to disk under a certain name. Later, we can retrieve the object by use of its name. The name of the directory under which the arrays are stored by joblib can be given by the user.

class Storage:

"""

Store large data structures (e.g. numpy arrays) efficiently

using joblib.

Use:

>>> from Storage import Storage

>>> storage = Storage(cachedir='tmp_u01', verbose=1)

>>> import numpy as np

>>> a = np.linspace(0, 1, 100000) # large array

>>> b = np.linspace(0, 1, 100000) # large array

>>> storage.save('a', a)

>>> storage.save('b', b)

>>> # later

>>> a = storage.retrieve('a')

>>> b = storage.retrieve('b')

"""

def __init__(self, cachedir="tmp", verbose=1):

"""

Parameters

----------

cachedir: str

Name of directory where objects are stored in files.

verbose: bool, int

Let joblib and this class speak when storing files

to disk.

"""

import joblib

self.memory = joblib.Memory(cachedir=cachedir, verbose=verbose)

self.verbose = verbose

self.retrieve = self.memory.cache(self.retrieve, ignore=["data"])

self.save = self.retrieve

def retrieve(self, name, data=None):

if self.verbose > 0:

print("joblib save of", name)

return dataThe retrieve and save functions, which do the work, seem quite magic. The idea is that joblib looks at the name parameter and saves the return value data to disk if the name parameter has not been used in a previous call. Otherwise, if name is already registered, joblib fetches the data object from file and returns it (this is an example of a memoize function, see Section 2.1.4 in (Langtangen and Pedersen 2016) for a brief explanation]).

11.7 Using a hash to create a file or directory name

Array storage techniques like those outlined in Sections Section 11.6 and Section 11.5.1 demand the user to assign a name for the file(s) or directory where the solution is to be stored. Ideally, this name should reflect parameters in the problem such that one can recognize an already run simulation. One technique is to make a hash string out of the input data. A hash string is a 40-character long hexadecimal string that uniquely reflects another potentially much longer string. (You may be used to hash strings from the Git version control system: every committed version of the files in Git is recognized by a hash string.)

Suppose you have some input data in the form of functions, numpy arrays, and other objects. To turn these input data into a string, we may grab the source code of the functions, use a very efficient hash method for potentially large arrays, and simply convert all other objects via str to a string representation. The final string, merging all input data, is then converted to an SHA1 hash string such that we represent the input with a 40-character long string.

def myfunction(func1, func2, array1, array2, obj1, obj2):

import inspect, joblib, hashlib

data = (inspect.getsource(func1),

inspect.getsource(func2),

joblib.hash(array1),

joblib.hash(array2),

str(obj1),

str(obj2))

hash_input = hashlib.sha1(data).hexdigest()It is wise to use joblib.hash and not try to do a str(array1), since that string can be very long, and joblib.hash is more efficient than hashlib when turning these data into a hash.

The idea of turning a function object into a string via its source code may look smart, but is not a completely reliable solution. Suppose we have some function

x0 = 0.1

f = lambda x: 0 if x <= x0 else 1The source code will be f = lambda x: 0 if x <= x0 else 1, so if the calling code changes the value of x0 (which f remembers - it is a closure), the source remains unchanged, the hash is the same, and the change in input data is unnoticed. Consequently, the technique above must be used with care. The user can always just remove the stored files in disk and thereby force a recomputation (provided the software applies a hash to test if a zip archive or joblib subdirectory exists, and if so, avoids recomputation).

We use numpy.storez to store the solution at each time level on disk. Such actions must be taken care of outside the solver function, more precisely in the user_action function that is called at every time level.

We have, in the wave1D_dn_vc.py code, implemented the user_action callback function as a class PlotAndStoreSolution with a __call__(self, x, t, t, n) method for the user_action function. Basically, __call__ stores and plots the solution. The storage makes use of the numpy.savez function for saving a set of arrays to a zip archive. Here, in this callback function, we want to save one array, u. Since there will be many such arrays, we introduce the array names 'u%04d' % n and closely related filenames. The usage of numpy.savez in __call__ goes like this:

from numpy import savez

name = 'u%04d' % n # array name

kwargs = {name: u} # keyword args for savez

fname = '.' + self.filename + '_' + name + '.dat'

self.t.append(t[n]) # store corresponding time value

savez(fname, **kwargs)

if n == 0: # store x once

savez('.' + self.filename + '_x.dat', x=x)For example, if n is 10 and self.filename is tmp, the above call to savez becomes savez('.tmp_u0010.dat', u0010=u). The actual filename becomes .tmp_u0010.dat.npz. The actual array name becomes u0010.npy.

Each savez call results in a file, so after the simulation we have one file per time level. Each file produced by savez is a zip archive. It makes sense to merge all the files into one. This is done in the close_file method in the PlotAndStoreSolution class. The code goes as follows.

class PlotAndStoreSolution:

...

def close_file(self, hashed_input):

"""

Merge all files from savez calls into one archive.

hashed_input is a string reflecting input data

for this simulation (made by solver).

"""

if self.filename is not None:

savez('.' + self.filename + '_t.dat',

t=array(self.t, dtype=float))

archive_name = '.' + hashed_input + '_archive.npz'

filenames = glob.glob('.' + self.filename + '*.dat.npz')

merge_zip_archives(filenames, archive_name)We use various ZipFile functionality to extract the content of the individual files (each with name filename) and write it to the merged archive (archive). There is only one array in each individual file (filename) so strictly speaking, there is no need for the loop for name in f.namelist() (as f.namelist() returns a list of length 1). However, in other applications where we compute more arrays at each time level, savez will store all these and then there is need for iterating over f.namelist().

Instead of merging the archives written by savez we could make an alternative implementation that writes all our arrays into one archive. This is the subject of Exercise Section 11.31.

11.8 Making hash strings from input data

The hashed_input argument, used to name the resulting archive file with all solutions, is supposed to be a hash reflecting all import parameters in the problem such that this simulation has a unique name. The hashed_input string is made in the solver function, using the hashlib and inspect modules, based on the arguments to solver:

import hashlib, inspect

data = inspect.getsource(I) + '_' + inspect.getsource(V) + \

'**' + inspect.getsource(f) + '**' + str(c) + '_' + \

('None' if U_0 is None else inspect.getsource(U_0)) + \

('None' if U_L is None else inspect.getsource(U_L)) + \

'**' + str(L) + str(dt) + '**' + str(C) + '_' + str(T) + \

'_' + str(stability_safety_factor)

hashed_input = hashlib.sha1(data).hexdigest()To get the source code of a function f as a string, we use inspect.getsource(f). All input, functions as well as variables, is then merged to a string data, and then hashlib.sha1 makes a unique, much shorter (40 characters long), fixed-length string out of data that we can use in the archive filename.

Note that the construction of the data string is not fool proof: if, e.g., I is a formula with parameters and the parameters change, the source code is still the same and data and hence the hash remains unaltered. The implementation must therefore be used with care!

11.9 Avoiding rerunning previously run cases

If the archive file whose name is based on hashed_input already exists, the simulation with the current set of parameters has been done before and one can avoid redoing the work. The solver function returns the CPU time and hashed_input, and a negative CPU time means that no simulation was run. In that case we should not call the close_file method above (otherwise we overwrite the archive with just the self.t array). The typical usage goes like

action = PlotAndStoreSolution(...)

dt = (L/Nx)/C # choose the stability limit with given Nx

cpu, hashed_input = solver(

I=lambda x: ...,

V=0, f=0, c=1, U_0=lambda t: 0, U_L=None, L=1,

dt=dt, C=C, T=T,

user_action=action, version='vectorized',

stability_safety_factor=1)

action.make_movie_file()

if cpu > 0: # did we generate new data?

action.close_file(hashed_input)11.10 Verification

11.10.1 Vanishing approximation error

Exact solutions of the numerical equations are always attractive for verification purposes since the software should reproduce such solutions to machine precision. With Dirichlet boundary conditions we can construct a function that is linear in \(t\) and quadratic in \(x\) that is also an exact solution of the scheme, while with Neumann conditions we are left with testing just a constant solution (see comments in Section 2.19).

11.10.2 Convergence rates

A more general method for verification is to check the convergence rates. We must introduce one discretization parameter \(h\) and assume an error model \(E=Ch^r\), where \(C\) and \(r\) are constants to be determine (i.e., \(r\) is the rate that we are interested in). Given two experiments with different resolutions \(h_i\) and \(h_i{-1}\), we can estimate \(r\) by \[

r = \frac{\ln(E_{i}/E_{i-1})}{\ln(h_{i}/h_{i-1})},

\] where \(E_i\) is the error corresponding to \(h_i\) and \(E_{i-1}\) corresponds to \(h_{i-1}\). Section 2.9 explains the details of this type of verification and how we introduce the single discretization parameter \(h=\Delta t = \hat c\Delta t\), for some constant \(\hat c\). To compute the error, we had to rely on a global variable in the user action function. Below is an implementation where we have a more elegant solution in terms of a class: the error variable is not a class attribute and there is no need for a global error (which is always considered an advantage).

def convergence_rates(

u_exact, # Function for exact solution

I, V, f, c, L, # Problem parameters

dt_values, # List of dt values to test

solver_function, # Solver to test

):

"""

Compute convergence rates for a wave equation solver.

Returns list of observed convergence rates.

"""

E_values = []

for dt in dt_values:

# Run solver and compute error

u, x, t = solver_function(I, V, f, c, L, dt, ...)

u_e = u_exact(x, t[-1])

E = np.sqrt(dt * np.sum((u_e - u) ** 2))

E_values.append(E)

# Compute convergence rates

r = [np.log(E_values[i] / E_values[i-1]) /

np.log(dt_values[i] / dt_values[i-1])

for i in range(1, len(dt_values))]

return rFor a complete, tested implementation of convergence rate testing with Devito, see src/wave/wave1D_devito.py and tests/test_wave_devito.py.

The returned sequence r should converge to 2 since the error analysis in Section 2.40 predicts various error measures to behave like \(\Oof{\Delta t^2} + \Oof{\Delta x^2}\). We can easily run the case with standing waves and the analytical solution \(u(x,t) = \cos(\frac{2\pi}{L}t)\sin(\frac{2\pi}{L}x)\). See Section 2.12.16 for details on convergence rate testing with Devito.

Many who know about class programming prefer to organize their software in terms of classes. This gives a richer application programming interface (API) since a function solver must have all its input data in terms of arguments, while a class-based solver naturally has a mix of method arguments and user-supplied methods. (Well, to be more precise, our solvers have demanded user_action to be a function provided by the user, so it is possible to mix variables and functions in the input also with a solver function.)

We will next illustrate how some of the functionality in wave1D_dn_vc.py may be implemented by using classes. Focusing on class implementation aspects, we restrict the example case to a simpler wave with constant wave speed \(c\). Applying the method of manufactured solutions, we test whether the class based implementation is able to compute the known exact solution within machine precision.

We will create a class Problem to hold the physical parameters of the problem and a class Solver to hold the numerical solution parameters besides the solver function itself. As the number of parameters increases, so does the amount of repetitive code. We therefore take the opportunity to illustrate how this may be counteracted by introducing a super class Parameters that allows code to be parameterized. In addition, it is convenient to collect the arrays that describe the mesh in a special Mesh class and make a class Function for a mesh function (mesh point values and its mesh). All the following code is found in wave1D_oo.py.

11.11 Class Parameters

The classes Problem and Solver both inherit class Parameters, which handles reading of parameters from the command line and has methods for setting and getting parameter values. Since processing dictionaries is easier than processing a collection of individual attributes, the class Parameters requires each class Problem and Solver to represent their parameters by dictionaries, one compulsory and two optional ones. The compulsory dictionary, self.prm, contains all parameters, while a second and optional dictionary, self.type, holds the associated object types, and a third and optional dictionary, self.help, stores help strings. The Parameters class may be implemented as follows:

class Parameters:

def __init__(self):

"""

Subclasses must initialize self.prm with

parameters and default values, self.type with

the corresponding types, and self.help with

the corresponding descriptions of parameters.

self.type and self.help are optional, but

self.prms must be complete and contain all parameters.

"""

pass

def ok(self):

"""Check if attr. prm, type, and help are defined."""

if (

hasattr(self, "prm")

and isinstance(self.prm, dict)

and hasattr(self, "type")

and isinstance(self.type, dict)

and hasattr(self, "help")

and isinstance(self.help, dict)

):

return True

else:

raise ValueError(

"The constructor in class %s does not "

"initialize the\ndictionaries "

"self.prm, self.type, self.help!" % self.__class__.__name__

)

def _illegal_parameter(self, name):

"""Raise exception about illegal parameter name."""

raise ValueError(

'parameter "%s" is not registered.\nLegal '

"parameters are\n%s" % (name, " ".join(list(self.prm.keys())))

)

def set(self, **parameters):

"""Set one or more parameters."""

for name in parameters:

if name in self.prm:

self.prm[name] = parameters[name]

else:

self._illegal_parameter(name)

def get(self, name):

"""Get one or more parameter values."""

if isinstance(name, (list, tuple)): # get many?

for n in name:

if n not in self.prm:

self._illegal_parameter(name)

return [self.prm[n] for n in name]

else:

if name not in self.prm:

self._illegal_parameter(name)

return self.prm[name]

def __getitem__(self, name):

"""Allow obj[name] indexing to look up a parameter."""

return self.get(name)

def __setitem__(self, name, value):

"""

Allow obj[name] = value syntax to assign a parameter's value.

"""

return self.set(name=value)

def define_command_line_options(self, parser=None):

self.ok()

if parser is None:

import argparse

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

for name in self.prm:

tp = self.type[name] if name in self.type else str

help = self.help[name] if name in self.help else None

parser.add_argument(

"--" + name, default=self.get(name), metavar=name, type=tp, help=help

)

return parser

def init_from_command_line(self, args):

for name in self.prm:

self.prm[name] = getattr(args, name)11.12 Class Problem

Inheriting the Parameters class, our class Problem is defined as:

class Problem(Parameters):

"""

Physical parameters for the wave equation

u_tt = (c**2*u_x)_x + f(x,t) with t in [0,T] and

x in (0,L). The problem definition is implied by

the method of manufactured solution, choosing

u(x,t)=x(L-x)(1+t/2) as our solution. This solution

should be exactly reproduced when c is const.

"""

def __init__(self):

self.prm = dict(L=2.5, c=1.5, T=18)

self.type = dict(L=float, c=float, T=float)

self.help = dict(

L="1D domain",

c="coefficient (wave velocity) in PDE",

T="end time of simulation",

)

def u_exact(self, x, t):

L = self["L"]

return x * (L - x) * (1 + 0.5 * t)

def I(self, x):

return self.u_exact(x, 0)

def V(self, x):

return 0.5 * self.u_exact(x, 0)

def f(self, x, t):

c = self["c"]

return 2 * (1 + 0.5 * t) * c**2

def U_0(self, t):

return self.u_exact(0, t)

U_L = None11.13 Class Mesh

The Mesh class can be made valid for a space-time mesh in any number of space dimensions. To make the class versatile, the constructor accepts either a tuple/list of number of cells in each spatial dimension or a tuple/list of cell spacings. In addition, we need the size of the hypercube mesh as a tuple/list of 2-tuples with lower and upper limits of the mesh coordinates in each direction. For 1D meshes it is more natural to just write the number of cells or the cell size and not wrap it in a list. We also need the time interval from t0 to T. Giving no spatial discretization information implies a time mesh only, and vice versa. The Mesh class with documentation and a doc test should now be self-explanatory:

import numpy as np

class Mesh:

"""

Holds data structures for a uniform mesh on a hypercube in

space, plus a uniform mesh in time.

======== ==================================================

Argument Explanation

======== ==================================================

L List of 2-lists of min and max coordinates

in each spatial direction.

T Final time in time mesh.

Nt Number of cells in time mesh.

dt Time step. Either Nt or dt must be given.

N List of number of cells in the spatial directions.

d List of cell sizes in the spatial directions.

Either N or d must be given.

======== ==================================================

Users can access all the parameters mentioned above, plus

``x[i]`` and ``t`` for the coordinates in direction ``i``

and the time coordinates, respectively.

Examples:

>>> from UniformFDMesh import Mesh

>>>

>>> # Simple space mesh

>>> m = Mesh(L=[0,1], N=4)

>>> print m.dump()

space: [0,1] N=4 d=0.25

>>>

>>> # Simple time mesh

>>> m = Mesh(T=4, dt=0.5)

>>> print m.dump()

time: [0,4] Nt=8 dt=0.5

>>>

>>> # 2D space mesh

>>> m = Mesh(L=[[0,1], [-1,1]], d=[0.5, 1])

>>> print m.dump()

space: [0,1]x[-1,1] N=2x2 d=0.5,1

>>>

>>> # 2D space mesh and time mesh

>>> m = Mesh(L=[[0,1], [-1,1]], d=[0.5, 1], Nt=10, T=3)

>>> print m.dump()

space: [0,1]x[-1,1] N=2x2 d=0.5,1 time: [0,3] Nt=10 dt=0.3

"""

def __init__(self, L=None, T=None, t0=0, N=None, d=None, Nt=None, dt=None):

if N is None and d is None:

if Nt is None and dt is None:

raise ValueError("Mesh constructor: either Nt or dt must be given")

if T is None:

raise ValueError("Mesh constructor: T must be given")

if Nt is None and dt is None:

if N is None and d is None:

raise ValueError("Mesh constructor: either N or d must be given")

if L is None:

raise ValueError("Mesh constructor: L must be given")

if L is not None and isinstance(L[0], (float, int)):

L = [L]

if N is not None and isinstance(N, (float, int)):

N = [N]

if d is not None and isinstance(d, (float, int)):

d = [d]

self.x = None

self.t = None

self.Nt = None

self.dt = None

self.N = None

self.d = None

self.t0 = t0

if N is None and d is not None and L is not None:

self.L = L

if len(d) != len(L):

raise ValueError(

"d has different size (no of space dim.) from L: %d vs %d",

len(d),

len(L),

)

self.d = d

self.N = [

int(round(float(self.L[i][1] - self.L[i][0]) / d[i]))

for i in range(len(d))

]

if d is None and N is not None and L is not None:

self.L = L

if len(N) != len(L):

raise ValueError(

"N has different size (no of space dim.) from L: %d vs %d",

len(N),

len(L),

)

self.N = N

self.d = [float(self.L[i][1] - self.L[i][0]) / N[i] for i in range(len(N))]

if Nt is None and dt is not None and T is not None:

self.T = T

self.dt = dt

self.Nt = int(round(T / dt))

if dt is None and Nt is not None and T is not None:

self.T = T

self.Nt = Nt

self.dt = T / float(Nt)

if self.N is not None:

self.x = [

np.linspace(self.L[i][0], self.L[i][1], self.N[i] + 1)

for i in range(len(self.L))

]

if Nt is not None:

self.t = np.linspace(self.t0, self.T, self.Nt + 1)

def get_num_space_dim(self):

return len(self.d) if self.d is not None else 0

def has_space(self):

return self.d is not None

def has_time(self):

return self.dt is not None

def dump(self):

s = ""

if self.has_space():

s += (

"space: "

+ "x".join(

["[%g,%g]" % (self.L[i][0], self.L[i][1]) for i in range(len(self.L))]

)

+ " N="

)

s += "x".join([str(Ni) for Ni in self.N]) + " d="

s += ",".join([str(di) for di in self.d])

if self.has_space() and self.has_time():

s += " "

if self.has_time():

s += (

"time: "

+ "[%g,%g]" % (self.t0, self.T)

+ " Nt=%g" % self.Nt

+ " dt=%g" % self.dt

)

return sJava programmers, in particular, are used to get/set functions in classes to access internal data. In Python, we usually apply direct access of the attribute, such as m.N[i] if m is a Mesh object. A widely used convention is to do this as long as access to an attribute does not require additional code. In that case, one applies a property construction. The original interface remains the same after a property is introduced (in contrast to Java), so user will not notice a change to properties.

The only argument against direct attribute access in class Mesh is that the attributes are read-only so we could avoid offering a set function. Instead, we rely on the user not to assign new values to the attributes.

11.14 Class Function

A class Function is handy to hold a mesh and corresponding values for a scalar or vector function over the mesh. Since we may have a time or space mesh, or a combined time and space mesh, with one or more components in the function, some if tests are needed for allocating the right array sizes. To help the user, an indices attribute with the name of the indices in the final array u for the function values is made. The examples in the doc string should explain the functionality.

class Function:

"""

A scalar or vector function over a mesh (of class Mesh).

========== ===================================================

Argument Explanation

========== ===================================================

mesh Class Mesh object: spatial and/or temporal mesh.

num_comp Number of components in function (1 for scalar).

space_only True if the function is defined on the space mesh

only (to save space). False if function has values

in space and time.

========== ===================================================

The indexing of ``u``, which holds the mesh point values of the

function, depends on whether we have a space and/or time mesh.

Examples:

>>> from UniformFDMesh import Mesh, Function

>>>

>>> # Simple space mesh

>>> m = Mesh(L=[0,1], N=4)

>>> print m.dump()

space: [0,1] N=4 d=0.25

>>> f = Function(m)

>>> f.indices

['x0']

>>> f.u.shape

(5,)

>>> f.u[4] # space point 4

0.0

>>>

>>> # Simple time mesh for two components

>>> m = Mesh(T=4, dt=0.5)

>>> print m.dump()

time: [0,4] Nt=8 dt=0.5

>>> f = Function(m, num_comp=2)

>>> f.indices

['time', 'component']

>>> f.u.shape

(9, 2)

>>> f.u[3,1] # time point 3, comp=1 (2nd comp.)

0.0

>>>

>>> # 2D space mesh

>>> m = Mesh(L=[[0,1], [-1,1]], d=[0.5, 1])

>>> print m.dump()

space: [0,1]x[-1,1] N=2x2 d=0.5,1

>>> f = Function(m)

>>> f.indices

['x0', 'x1']

>>> f.u.shape

(3, 3)

>>> f.u[1,2] # space point (1,2)

0.0

>>>

>>> # 2D space mesh and time mesh

>>> m = Mesh(L=[[0,1],[-1,1]], d=[0.5,1], Nt=10, T=3)

>>> print m.dump()

space: [0,1]x[-1,1] N=2x2 d=0.5,1 time: [0,3] Nt=10 dt=0.3

>>> f = Function(m, num_comp=2, space_only=False)

>>> f.indices

['time', 'x0', 'x1', 'component']

>>> f.u.shape

(11, 3, 3, 2)

>>> f.u[2,1,2,0] # time step 2, space point (1,2), comp=0

0.0

>>> # Function with space data only

>>> f = Function(m, num_comp=1, space_only=True)

>>> f.indices

['x0', 'x1']

>>> f.u.shape

(3, 3)

>>> f.u[1,2] # space point (1,2)

0.0

"""

def __init__(self, mesh, num_comp=1, space_only=True):

self.mesh = mesh

self.num_comp = num_comp

self.indices = []

if (self.mesh.has_space() and not self.mesh.has_time()) or (

self.mesh.has_space() and self.mesh.has_time() and space_only

):

if num_comp == 1:

self.u = np.zeros([self.mesh.N[i] + 1 for i in range(len(self.mesh.N))])

self.indices = ["x" + str(i) for i in range(len(self.mesh.N))]

else:

self.u = np.zeros(

[self.mesh.N[i] + 1 for i in range(len(self.mesh.N))] + [num_comp]

)

self.indices = ["x" + str(i) for i in range(len(self.mesh.N))] + [

"component"

]

if not self.mesh.has_space() and self.mesh.has_time():

if num_comp == 1:

self.u = np.zeros(self.mesh.Nt + 1)

self.indices = ["time"]

else:

self.u = np.zeros((self.mesh.Nt + 1, num_comp))

self.indices = ["time", "component"]

if self.mesh.has_space() and self.mesh.has_time() and not space_only:

size = [self.mesh.Nt + 1] + [

self.mesh.N[i] + 1 for i in range(len(self.mesh.N))

]

if num_comp > 1:

self.indices = (

["time"]

+ ["x" + str(i) for i in range(len(self.mesh.N))]

+ ["component"]

)

size += [num_comp]

else:

self.indices = ["time"] + ["x" + str(i) for i in range(len(self.mesh.N))]

self.u = np.zeros(size)11.15 Class Solver

With the Mesh and Function classes in place, we can rewrite the solver function, but we make it a method in class Solver:

class Solver(Parameters):

"""

Numerical parameters for solving the wave equation

u_tt = (c**2*u_x)_x + f(x,t) with t in [0,T] and

x in (0,L). The problem definition is implied by

the method of manufactured solution, choosing

u(x,t)=x(L-x)(1+t/2) as our solution. This solution

should be exactly reproduced, provided c is const.

We simulate in [0, L/2] and apply a symmetry condition

at the end x=L/2.

"""

def __init__(self, problem):

self.problem = problem

self.prm = dict(C=0.75, Nx=3, stability_safety_factor=1.0)

self.type = dict(C=float, Nx=int, stability_safety_factor=float)

self.help = dict(

C="Courant number",

Nx="No of spatial mesh points",

stability_safety_factor="stability factor",

)

from UniformFDMesh import Function, Mesh

L_end = self.problem["L"]

dx = (L_end / 2) / float(self["Nx"])

t_interval = self.problem["T"]

dt = dx * self["stability_safety_factor"] * self["C"] / float(self.problem["c"])

self.m = Mesh(

L=[0, L_end / 2], d=[dx], Nt=int(round(t_interval / float(dt))), T=t_interval

)

self.f = Function(self.m, num_comp=1, space_only=False)

def solve(self, user_action=None, version="scalar"):

L, c, T = self.problem[["L", "c", "T"]]

L = L / 2 # compute with half the domain only (symmetry)

C, Nx, stability_safety_factor = self[["C", "Nx", "stability_safety_factor"]]

dx = self.m.d[0]

I = self.problem.I

V = self.problem.V

f = self.problem.f

U_0 = self.problem.U_0

U_L = self.problem.U_L

Nt = self.m.Nt

t = np.linspace(0, T, Nt + 1) # Mesh points in time

x = np.linspace(0, L, Nx + 1) # Mesh points in space

dx = x[1] - x[0]

dt = t[1] - t[0]

if isinstance(c, (float, int)):

c = np.zeros(x.shape) + c

elif callable(c):

c_ = np.zeros(x.shape)

for i in range(Nx + 1):

c_[i] = c(x[i])

c = c_

q = c**2

C2 = (dt / dx) ** 2

dt2 = dt * dt # Help variables in the scheme

if f is None or f == 0:

f = (

(lambda x, t: 0)

if version == "scalar"

else lambda x, t: np.zeros(x.shape)

)

if I is None or I == 0:

I = (lambda x: 0) if version == "scalar" else lambda x: np.zeros(x.shape)

if V is None or V == 0:

V = (lambda x: 0) if version == "scalar" else lambda x: np.zeros(x.shape)

if U_0 is not None:

if isinstance(U_0, (float, int)) and U_0 == 0:

U_0 = lambda t: 0

if U_L is not None:

if isinstance(U_L, (float, int)) and U_L == 0:

U_L = lambda t: 0

import hashlib

import inspect

data = (

inspect.getsource(I)

+ "_"

+ inspect.getsource(V)

+ "_"

+ inspect.getsource(f)

+ "_"

+ str(c)

+ "_"

+ ("None" if U_0 is None else inspect.getsource(U_0))

+ ("None" if U_L is None else inspect.getsource(U_L))

+ "_"

+ str(L)

+ str(dt)

+ "_"

+ str(C)

+ "_"

+ str(T)

+ "_"

+ str(stability_safety_factor)

)

hashed_input = hashlib.sha1(data).hexdigest()

if os.path.isfile("." + hashed_input + "_archive.npz"):

return -1, hashed_input

u_1 = self.f.u[0, :]

u = self.f.u[1, :]

t0 = time.perf_counter() # CPU time measurement

Ix = range(0, Nx + 1)

It = range(0, Nt + 1)

for i in range(0, Nx + 1):

u_1[i] = I(x[i])

if user_action is not None:

user_action(u_1, x, t, 0)

for i in Ix[1:-1]:

u[i] = (

u_1[i]

+ dt * V(x[i])

+ 0.5

* C2

* (

0.5 * (q[i] + q[i + 1]) * (u_1[i + 1] - u_1[i])

- 0.5 * (q[i] + q[i - 1]) * (u_1[i] - u_1[i - 1])

)

+ 0.5 * dt2 * f(x[i], t[0])

)

i = Ix[0]

if U_0 is None:

ip1 = i + 1

im1 = ip1 # i-1 -> i+1

u[i] = (

u_1[i]

+ dt * V(x[i])

+ 0.5

* C2

* (

0.5 * (q[i] + q[ip1]) * (u_1[ip1] - u_1[i])

- 0.5 * (q[i] + q[im1]) * (u_1[i] - u_1[im1])

)

+ 0.5 * dt2 * f(x[i], t[0])

)

else:

u[i] = U_0(dt)

i = Ix[-1]

if U_L is None:

im1 = i - 1

ip1 = im1 # i+1 -> i-1

u[i] = (

u_1[i]

+ dt * V(x[i])

+ 0.5

* C2

* (

0.5 * (q[i] + q[ip1]) * (u_1[ip1] - u_1[i])

- 0.5 * (q[i] + q[im1]) * (u_1[i] - u_1[im1])

)

+ 0.5 * dt2 * f(x[i], t[0])

)

else:

u[i] = U_L(dt)

if user_action is not None:

user_action(u, x, t, 1)

for n in It[1:-1]:

u_2 = self.f.u[n - 1, :]

u_1 = self.f.u[n, :]

u = self.f.u[n + 1, :]

if version == "scalar":

for i in Ix[1:-1]:

u[i] = (

-u_2[i]

+ 2 * u_1[i]

+ C2

* (

0.5 * (q[i] + q[i + 1]) * (u_1[i + 1] - u_1[i])

- 0.5 * (q[i] + q[i - 1]) * (u_1[i] - u_1[i - 1])

)

+ dt2 * f(x[i], t[n])

)

elif version == "vectorized":

u[1:-1] = (

-u_2[1:-1]

+ 2 * u_1[1:-1]

+ C2

* (

0.5 * (q[1:-1] + q[2:]) * (u_1[2:] - u_1[1:-1])

- 0.5 * (q[1:-1] + q[:-2]) * (u_1[1:-1] - u_1[:-2])

)

+ dt2 * f(x[1:-1], t[n])

)

else:

raise ValueError("version=%s" % version)

i = Ix[0]

if U_0 is None:

ip1 = i + 1

im1 = ip1

u[i] = (

-u_2[i]

+ 2 * u_1[i]

+ C2

* (

0.5 * (q[i] + q[ip1]) * (u_1[ip1] - u_1[i])

- 0.5 * (q[i] + q[im1]) * (u_1[i] - u_1[im1])

)

+ dt2 * f(x[i], t[n])

)

else:

u[i] = U_0(t[n + 1])

i = Ix[-1]

if U_L is None:

im1 = i - 1

ip1 = im1

u[i] = (

-u_2[i]

+ 2 * u_1[i]

+ C2

* (

0.5 * (q[i] + q[ip1]) * (u_1[ip1] - u_1[i])

- 0.5 * (q[i] + q[im1]) * (u_1[i] - u_1[im1])

)

+ dt2 * f(x[i], t[n])

)

else:

u[i] = U_L(t[n + 1])

if user_action is not None:

if user_action(u, x, t, n + 1):

break

cpu_time = time.perf_counter() - t0

return cpu_time, hashed_input

def assert_no_error(self):

"""Run through mesh and check error"""

Nx = self["Nx"]

Nt = self.m.Nt

L, T = self.problem[["L", "T"]]

L = L / 2 # only half the domain used (symmetry)

x = np.linspace(0, L, Nx + 1) # Mesh points in space

t = np.linspace(0, T, Nt + 1) # Mesh points in time

for n in range(len(t)):

u_e = self.problem.u_exact(x, t[n])

diff = np.abs(self.f.u[n, :] - u_e).max()

print("diff:", diff)

tol = 1e-13

assert diff < tolObserve that the solutions from all time steps are stored in the mesh function, which allows error assessment (in assert_no_error) to take place after all solutions have been found. Of course, in 2D or 3D, such a strategy may place too high demands on available computer memory, in which case intermediate results could be stored on file.

Running wave1D_oo.py gives a printout showing that the class-based implementation performs as expected, i.e. that the known exact solution is reproduced (within machine precision).

11.16 Speeding up Cython code

We now consider the wave2D_u0.py code for solving the 2D linear wave equation with constant wave velocity and homogeneous Dirichlet boundary conditions \(u=0\). We shall in the present chapter extend this code with computational modules written in other languages than Python. This extended version is called wave2D_u0_adv.py.

The wave2D_u0.py file contains a solver function, which calls an advance_* function to advance the numerical scheme one level forward in time. The function advance_scalar applies standard Python loops to implement the scheme, while advance_vectorized performs corresponding vectorized arithmetics with array slices. The statements of this solver are explained in Section 2.46.

Although vectorization can bring down the CPU time dramatically compared with scalar code, there is still some factor 5-10 to win in these types of applications by implementing the finite difference scheme in compiled code, typically in Fortran, C, or C++. This can quite easily be done by adding a little extra code to our program. Cython is an extension of Python that offers the easiest way to nail our Python loops in the scalar code down to machine code and achieve the efficiency of C.

Cython can be viewed as an extended Python language where variables are declared with types and where functions are marked to be implemented in C. Migrating Python code to Cython is done by copying the desired code segments to functions (or classes) and placing them in one or more separate files with extension .pyx.

11.17 Declaring variables and annotating the code

Our starting point is the plain advance_scalar function for a scalar implementation of the updating algorithm for new values \(u^{n+1}_{i,j}\):

def advance_scalar(u, u_n, u_nm1, f, x, y, t, n, Cx2, Cy2, dt2,

V=None, step1=False):

Ix = range(0, u.shape[0]); It = range(0, u.shape[1])

if step1:

dt = sqrt(dt2) # save

Cx2 = 0.5*Cx2; Cy2 = 0.5*Cy2; dt2 = 0.5*dt2 # redefine

D1 = 1; D2 = 0

else:

D1 = 2; D2 = 1

for i in Ix[1:-1]:

for j in It[1:-1]:

u_xx = u_n[i-1,j] - 2*u_n[i,j] + u_n[i+1,j]

u_yy = u_n[i,j-1] - 2*u_n[i,j] + u_n[i,j+1]

u[i,j] = D1*u_n[i,j] - D2*u_nm1[i,j] + \

Cx2*u_xx + Cy2*u_yy + dt2*f(x[i], y[j], t[n])

if step1:

u[i,j] += dt*V(x[i], y[j])

j = It[0]

for i in Ix: u[i,j] = 0

j = It[-1]

for i in Ix: u[i,j] = 0

i = Ix[0]

for j in It: u[i,j] = 0

i = Ix[-1]

for j in It: u[i,j] = 0

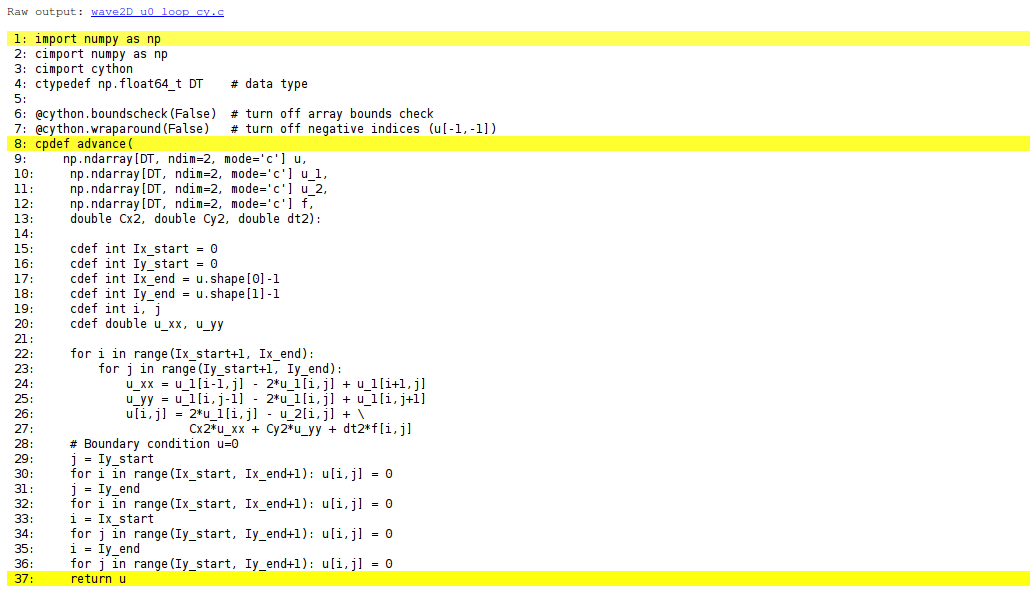

return uWe simply take a copy of this function and put it in a file wave2D_u0_loop_cy.pyx. The relevant Cython implementation arises from declaring variables with types and adding some important annotations to speed up array computing in Cython. Let us first list the complete code in the .pyx file:

import numpy as np

cimport cython

cimport numpy as np

ctypedef np.float64_t DT # data type

@cython.boundscheck(False) # turn off array bounds check

@cython.wraparound(False) # turn off negative indices (u[-1,-1])

cpdef advance(

np.ndarray[DT, ndim=2, mode='c'] u,

np.ndarray[DT, ndim=2, mode='c'] u_1,

np.ndarray[DT, ndim=2, mode='c'] u_2,

np.ndarray[DT, ndim=2, mode='c'] f,

double Cx2, double Cy2, double dt2):

cdef:

int Ix_start = 0

int It_start = 0

int Ix_end = u.shape[0]-1

int It_end = u.shape[1]-1

int i, j

double u_xx, u_yy

for i in range(Ix_start+1, Ix_end):

for j in range(It_start+1, It_end):

u_xx = u_1[i-1,j] - 2*u_1[i,j] + u_1[i+1,j]

u_yy = u_1[i,j-1] - 2*u_1[i,j] + u_1[i,j+1]

u[i,j] = 2*u_1[i,j] - u_2[i,j] + \

Cx2*u_xx + Cy2*u_yy + dt2*f[i,j]

j = It_start

for i in range(Ix_start, Ix_end+1): u[i,j] = 0

j = It_end

for i in range(Ix_start, Ix_end+1): u[i,j] = 0

i = Ix_start

for j in range(It_start, It_end+1): u[i,j] = 0

i = Ix_end

for j in range(It_start, It_end+1): u[i,j] = 0

return uThis example may act as a recipe on how to transform array-intensive code with loops into Cython.

- Variables are declared with types: for example,

double vin the argument list instead of justv, andcdef double vfor a variablevin the body of the function. A Pythonfloatobject is declared asdoublefor translation to C by Cython, while anintobject is declared byint. - Arrays need a comprehensive type declaration involving

- the type

np.ndarray, - the data type of the elements, here 64-bit floats, abbreviated as

DTthroughctypedef np.float64_t DT(instead ofDTwe could use the full name of the data type:np.float64_t, which is a Cython-defined type), - the dimensions of the array, here

ndim=2andndim=1, - specification of contiguous memory for the array (

mode='c').

- Functions declared with

cpdefare translated to C but are also accessible from Python. - In addition to the standard

numpyimport we also need a special Cython import ofnumpy:cimport numpy as np, to appear after the standard import. - By default, array indices are checked to be within their legal limits. To speed up the code one should turn off this feature for a specific function by placing

@cython.boundscheck(False)above the function header. - Also by default, array indices can be negative (counting from the end), but this feature has a performance penalty and is therefore here turned off by writing

@cython.wraparound(False)right above the function header. - The use of index sets

IxandItin the scalar code cannot be successfully translated to C. One reason is that constructions likeIx[1:-1]involve negative indices, and these are now turned off. Another reason is that Cython loops must take the formfor i in xrangeorfor i in rangefor being translated into efficient C loops. We have therefore introducedIx_startasIx[0]andIx_endasIx[-1]to hold the start and end of the values of index \(i\). Similar variables are introduced for the \(j\) index. A loopfor i in Ixis with these new variables written asfor i in range(Ix_start, Ix_end+1).

We have used the syntax np.ndarray[DT, ndim=2, mode='c'] to declare numpy arrays in Cython. There is a simpler, alternative syntax, employing typed memory views, where the declaration looks like double [:,:]. However, the full support for this functionality is not yet ready, and in this text we use the full array declaration syntax.

11.18 Visual inspection of the C translation

Cython can visually explain how successfully it translated a code from Python to C. The command

Terminal> cython -a wave2D_u0_loop_cy.pyxproduces an HTML file wave2D_u0_loop_cy.html, which can be loaded into a web browser to illustrate which lines of the code that have been translated to C. Figure Figure 11.1 shows the illustrated code. Yellow lines indicate the lines that Cython did not manage to translate to efficient C code and that remain in Python. For the present code we see that Cython is able to translate all the loops with array computing to C, which is our primary goal.

You can also inspect the generated C code directly, as it appears in the file wave2D_u0_loop_cy.c. Nevertheless, understanding this C code requires some familiarity with writing Python extension modules in C by hand. Deep down in the file we can see in detail how the compute-intensive statements have been translated into some complex C code that is quite different from what a human would write (at least if a direct correspondence to the mathematical notation was intended).

11.19 Building the extension module

Cython code must be translated to C, compiled, and linked to form what is known in the Python world as a C extension module. This is usually done by making a setup.py script, which is the standard way of building and installing Python software. For an extension module arising from Cython code, the following setup.py script is all we need to build and install the module:

from distutils.core import setup

from distutils.extension import Extension

from Cython.Distutils import build_ext

cymodule = 'wave2D_u0_loop_cy'

setup(

name=cymodule

ext_modules=[Extension(cymodule, [cymodule + '.pyx'],)],

cmdclass={'build_ext': build_ext},

)We run the script by

Terminal> python setup.py build_ext --inplaceThe --inplace option makes the extension module available in the current directory as the file wave2D_u0_loop_cy.so. This file acts as a normal Python module that can be imported and inspected:

>>> import wave2D_u0_loop_cy

>>> dir(wave2D_u0_loop_cy)

['__builtins__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__name__',

'__package__', '__test__', 'advance', 'np']The important output from the dir function is our Cython function advance (the module also features the imported numpy module under the name np as well as many standard Python objects with double underscores in their names).

The setup.py file makes use of the distutils package in Python and Cython’s extension of this package. These tools know how Python was built on the computer and will use compatible compiler(s) and options when building other code in Cython, C, or C++. Quite some experience with building large program systems is needed to do the build process manually, so using a setup.py script is strongly recommended.

When there is no need to link the C code with special libraries, Cython offers a shortcut for generating and importing the extension module:

import pyximport; pyximport.install()This makes the setup.py script redundant. However, in the wave2D_u0_adv.py code we do not use pyximport and require an explicit build process of this and many other modules.

11.20 Calling the Cython function from Python

The wave2D_u0_loop_cy module contains our advance function, which we now may call from the Python program for the wave equation:

import wave2D_u0_loop_cy

advance = wave2D_u0_loop_cy.advance

...

for n in It[1:-1]: # time loop

f_a[:,:] = f(xv, yv, t[n]) # precompute, size as u

u = advance(u, u_n, u_nm1, f_a, x, y, t, Cx2, Cy2, dt2)11.20.1 Efficiency

For a mesh consisting of \(120\times 120\) cells, the scalar Python code requires 1370 CPU time units, the vectorized version requires 5.5, while the Cython version requires only 1! For a smaller mesh with \(60\times 60\) cells Cython is about 1000 times faster than the scalar Python code, and the vectorized version is about 6 times slower than the Cython version.

Instead of relying on Cython’s (excellent) ability to translate Python to C, we can invoke a compiled language directly and write the loops ourselves. Let us start with Fortran 77, because this is a language with more convenient array handling than C (or plain C++), because we can use the same multi-dimensional indices in the Fortran code as in the numpy arrays in the Python code, while in C these arrays are one-dimensional and require us to reduce multi-dimensional indices to a single index.

11.21 The Fortran subroutine

We write a Fortran subroutine advance in a file wave2D_u0_loop_f77.f for implementing the updating formula (2.69) and setting the solution to zero at the boundaries:

subroutine advance(u, u_1, u_2, f, Cx2, Cy2, dt2, Nx, Ny)

integer Nx, Ny

real*8 u(0:Nx,0:Ny), u_1(0:Nx,0:Ny), u_2(0:Nx,0:Ny)

real*8 f(0:Nx,0:Ny), Cx2, Cy2, dt2

integer i, j

real*8 u_xx, u_yy

Cf2py intent(in, out) u

C Scheme at interior points

do j = 1, Ny-1

do i = 1, Nx-1

u_xx = u_1(i-1,j) - 2*u_1(i,j) + u_1(i+1,j)

u_yy = u_1(i,j-1) - 2*u_1(i,j) + u_1(i,j+1)

u(i,j) = 2*u_1(i,j) - u_2(i,j) + Cx2*u_xx + Cy2*u_yy +

& dt2*f(i,j)

end do

end do

C Boundary conditions

j = 0

do i = 0, Nx

u(i,j) = 0

end do

j = Ny

do i = 0, Nx

u(i,j) = 0

end do

i = 0

do j = 0, Ny

u(i,j) = 0

end do

i = Nx

do j = 0, Ny

u(i,j) = 0

end do

return

endThis code is plain Fortran 77, except for the special Cf2py comment line, which here specifies that u is both an input argument and an object to be returned from the advance routine. Or more precisely, Fortran is not able return an array from a function, but we need a wrapper code in C for the Fortran subroutine to enable calling it from Python, and from this wrapper code one can return u to the calling Python code.

It is not strictly necessary to return u to the calling Python code since the advance function will modify the elements of u, but the convention in Python is to get all output from a function as returned values. That is, the right way of calling the above Fortran subroutine from Python is

u = advance(u, u_n, u_nm1, f, Cx2, Cy2, dt2)The less encouraged style, which works and resembles the way the Fortran subroutine is called from Fortran, reads

advance(u, u_n, u_nm1, f, Cx2, Cy2, dt2)11.22 Building the Fortran module with f2py

The nice feature of writing loops in Fortran is that, without much effort, the tool f2py can produce a C extension module such that we can call the Fortran version of advance from Python. The necessary commands to run are

Terminal> f2py -m wave2D_u0_loop_f77 -h wave2D_u0_loop_f77.pyf \

--overwrite-signature wave2D_u0_loop_f77.f

Terminal> f2py -c wave2D_u0_loop_f77.pyf --build-dir build_f77 \

-DF2PY_REPORT_ON_ARRAY_COPY=1 wave2D_u0_loop_f77.fThe first command asks f2py to interpret the Fortran code and make a Fortran 90 specification of the extension module in the file wave2D_u0_loop_f77.pyf. The second command makes f2py generate all necessary wrapper code, compile our Fortran file and the wrapper code, and finally build the module. The build process takes place in the specified subdirectory build_f77 so that files can be inspected if something goes wrong. The option -DF2PY_REPORT_ON_ARRAY_COPY=1 makes f2py write a message for every array that is copied in the communication between Fortran and Python, which is very useful for avoiding unnecessary array copying (see below). The name of the module file is wave2D_u0_loop_f77.so, and this file can be imported and inspected as any other Python module:

>>> import wave2D_u0_loop_f77

>>> dir(wave2D_u0_loop_f77)

['__doc__', '__file__', '__name__', '__package__',

'__version__', 'advance']

>>> print wave2D_u0_loop_f77.__doc__

This module 'wave2D_u0_loop_f77' is auto-generated with f2py....

Functions:

u = advance(u,u_n,u_nm1,f,cx2,cy2,dt2,

nx=(shape(u,0)-1),ny=(shape(u,1)-1))Printing the doc strings of the module and its functions is extremely important after having created a module with f2py. The reason is that f2py makes Python interfaces to the Fortran functions that are different from how the functions are declared in the Fortran code (!). The rationale for this behavior is that f2py creates Pythonic interfaces such that Fortran routines can be called in the same way as one calls Python functions. Output data from Python functions is always returned to the calling code, but this is technically impossible in Fortran. Also, arrays in Python are passed to Python functions without their dimensions because that information is packed with the array data in the array objects. This is not possible in Fortran, however. Therefore, f2py removes array dimensions from the argument list, and f2py makes it possible to return objects back to Python.

Let us follow the advice of examining the doc strings and take a close look at the documentation f2py has generated for our Fortran advance subroutine:

>>> print wave2D_u0_loop_f77.advance.__doc__

This module 'wave2D_u0_loop_f77' is auto-generated with f2py

Functions:

u = advance(u,u_n,u_nm1,f,cx2,cy2,dt2,

nx=(shape(u,0)-1),ny=(shape(u,1)-1))

.

advance - Function signature:

u = advance(u,u_n,u_nm1,f,cx2,cy2,dt2,[nx,ny])

Required arguments:

u : input rank-2 array('d') with bounds (nx + 1,ny + 1)

u_n : input rank-2 array('d') with bounds (nx + 1,ny + 1)

u_nm1 : input rank-2 array('d') with bounds (nx + 1,ny + 1)

f : input rank-2 array('d') with bounds (nx + 1,ny + 1)

cx2 : input float

cy2 : input float

dt2 : input float

Optional arguments:

nx := (shape(u,0)-1) input int

ny := (shape(u,1)-1) input int

Return objects:

u : rank-2 array('d') with bounds (nx + 1,ny + 1)Here we see that the nx and ny parameters declared in Fortran are optional arguments that can be omitted when calling advance from Python.

We strongly recommend to print out the documentation of every Fortran function to be called from Python and make sure the call syntax is exactly as listed in the documentation.

11.23 How to avoid array copying

Multi-dimensional arrays are stored as a stream of numbers in memory. For a two-dimensional array consisting of rows and columns there are two ways of creating such a stream: row-major ordering, which means that rows are stored consecutively in memory, or column-major ordering, which means that the columns are stored one after each other. All programming languages inherited from C, including Python, apply the row-major ordering, but Fortran uses column-major storage. Thinking of a two-dimensional array in Python or C as a matrix, it means that Fortran works with the transposed matrix.

Fortunately, f2py creates extra code so that accessing u(i,j) in the Fortran subroutine corresponds to the element u[i,j] in the underlying numpy array (without the extra code, u(i,j) in Fortran would access u[j,i] in the numpy array). Technically, f2py takes a copy of our numpy array and reorders the data before sending the array to Fortran. Such copying can be costly. For 2D wave simulations on a \(60\times 60\) grid the overhead of copying is a factor of 5, which means that almost the whole performance gain of Fortran over vectorized numpy code is lost!

To avoid having f2py to copy arrays with C storage to the corresponding Fortran storage, we declare the arrays with Fortran storage:

order = 'Fortran' if version == 'f77' else 'C'

u = zeros((Nx+1,Ny+1), order=order) # solution array

u_n = zeros((Nx+1,Ny+1), order=order) # solution at t-dt

u_nm1 = zeros((Nx+1,Ny+1), order=order) # solution at t-2*dtIn the compile and build step of using f2py, it is recommended to add an extra option for making f2py report on array copying:

Terminal> f2py -c wave2D_u0_loop_f77.pyf --build-dir build_f77 \

-DF2PY_REPORT_ON_ARRAY_COPY=1 wave2D_u0_loop_f77.fIt can sometimes be a challenge to track down which array that causes a copying. There are two principal reasons for copying array data: either the array does not have Fortran storage or the element types do not match those declared in the Fortran code. The latter cause is usually effectively eliminated by using real*8 data in the Fortran code and float64 (the default float type in numpy) in the arrays on the Python side. The former reason is more common, and to check whether an array before a Fortran call has the right storage one can print the result of isfortran(a), which is True if the array a has Fortran storage.

Let us look at an example where we face problems with array storage. A typical problem in the wave2D_u0.py code is to set

f_a = f(xv, yv, t[n])before the call to the Fortran advance routine. This computation creates a new array with C storage. An undesired copy of f_a will be produced when sending f_a to a Fortran routine. There are two remedies, either direct insertion of data in an array with Fortran storage,

f_a = zeros((Nx+1, Ny+1), order='Fortran')

...

f_a[:,:] = f(xv, yv, t[n])or remaking the f(xv, yv, t[n]) array,

f_a = asarray(f(xv, yv, t[n]), order='Fortran')The former remedy is most efficient if the asarray operation is to be performed a large number of times.

11.23.1 Efficiency

The efficiency of this Fortran code is very similar to the Cython code. There is usually nothing more to gain, from a computational efficiency point of view, by implementing the complete Python program in Fortran or C. That will just be a lot more code for all administering work that is needed in scientific software, especially if we extend our sample program wave2D_u0.py to handle a real scientific problem. Then only a small portion will consist of loops with intensive array calculations. These can be migrated to Cython or Fortran as explained, while the rest of the programming can be more conveniently done in Python.

The computationally intensive loops can alternatively be implemented in C code. Just as Fortran calls for care regarding the storage of two-dimensional arrays, working with two-dimensional arrays in C is a bit tricky. The reason is that numpy arrays are viewed as one-dimensional arrays when transferred to C, while C programmers will think of u, u_n, and u_nm1 as two dimensional arrays and index them like u[i][j]. The C code must declare u as double* u and translate an index pair [i][j] to a corresponding single index when u is viewed as one-dimensional. This translation requires knowledge of how the numbers in u are stored in memory.

11.24 Translating index pairs to single indices

Two-dimensional numpy arrays with the default C storage are stored row by row. In general, multi-dimensional arrays with C storage are stored such that the last index has the fastest variation, then the next last index, and so on, ending up with the slowest variation in the first index. For a two-dimensional u declared as zeros((Nx+1,Ny+1)) in Python, the individual elements are stored in the following order:

u[0,0], u[0,1], u[0,2], ..., u[0,Ny], u[1,0], u[1,1], ...,

u[1,Ny], u[2,0], ..., u[Nx,0], u[Nx,1], ..., u[Nx, Ny]Viewing u as one-dimensional, the index pair \((i,j)\) translates to \(i(N_y+1)+j\). So, where a C programmer would naturally write an index u[i][j], the indexing must read u[i*(Ny+1) + j]. This is tedious to write, so it can be handy to define a C macro,

so that we can write u[idx(i,j)], which reads much better and is easier to debug.

Macros just perform simple text substitutions: idx(hello,world) is expanded to (hello)*(Ny+1) + world. The parentheses in (i) are essential - using the natural mathematical formula i*(Ny+1) + j in the macro definition, idx(i-1,j) would expand to i-1*(Ny+1) + j, which is the wrong formula. Macros are handy, but require careful use. In C++, inline functions are safer and replace the need for macros.

11.25 The complete C code

The C version of our function advance can be coded as follows.

void advance(double* u, double* u_1, double* u_2, double* f,

double Cx2, double Cy2, double dt2, int Nx, int Ny)

{

int i, j;

double u_xx, u_yy;

/* Scheme at interior points */

for (i=1; i<=Nx-1; i++) {

for (j=1; j<=Ny-1; j++) {

u_xx = u_1[idx(i-1,j)] - 2*u_1[idx(i,j)] + u_1[idx(i+1,j)];

u_yy = u_1[idx(i,j-1)] - 2*u_1[idx(i,j)] + u_1[idx(i,j+1)];

u[idx(i,j)] = 2*u_1[idx(i,j)] - u_2[idx(i,j)] +

Cx2*u_xx + Cy2*u_yy + dt2*f[idx(i,j)];

}

}

/* Boundary conditions */

j = 0; for (i=0; i<=Nx; i++) u[idx(i,j)] = 0;

j = Ny; for (i=0; i<=Nx; i++) u[idx(i,j)] = 0;

i = 0; for (j=0; j<=Ny; j++) u[idx(i,j)] = 0;

i = Nx; for (j=0; j<=Ny; j++) u[idx(i,j)] = 0;

}11.26 The Cython interface file

All the code above appears in the file wave2D_u0_loop_c.c. We need to compile this file together with C wrapper code such that advance can be called from Python. Cython can be used to generate appropriate wrapper code. The relevant Cython code for interfacing C is placed in a file with extension .pyx. This file, called wave2D_u0_loop_c_cy.pyx, looks like

import numpy as np

cimport cython

cimport numpy as np

cdef extern from "wave2D_u0_loop_c.h":

void advance(double* u, double* u_1, double* u_2, double* f,

double Cx2, double Cy2, double dt2,

int Nx, int Ny)

@cython.boundscheck(False)

@cython.wraparound(False)

def advance_cwrap(

np.ndarray[double, ndim=2, mode='c'] u,

np.ndarray[double, ndim=2, mode='c'] u_1,

np.ndarray[double, ndim=2, mode='c'] u_2,

np.ndarray[double, ndim=2, mode='c'] f,

double Cx2, double Cy2, double dt2):

advance(&u[0,0], &u_1[0,0], &u_2[0,0], &f[0,0],

Cx2, Cy2, dt2,

u.shape[0]-1, u.shape[1]-1)

return uWe first declare the C functions to be interfaced. These must also appear in a C header file, wave2D_u0_loop_c.h,

extern void advance(double* u, double* u_n, double* u_nm1, double* f,

double Cx2, double Cy2, double dt2,

int Nx, int Ny);The next step is to write a Cython function with Python objects as arguments. The name advance is already used for the C function so the function to be called from Python is named advance_cwrap. The contents of this function is simply a call to the advance version in C. To this end, the right information from the Python objects must be passed on as arguments to advance. Arrays are sent with their C pointers to the first element, obtained in Cython as &u[0,0] (the & takes the address of a C variable). The Nx and Ny arguments in advance are easily obtained from the shape of the numpy array u. Finally, u must be returned such that we can set u = advance(...) in Python.

11.27 Building the extension module

It remains to build the extension module. An appropriate setup.py file is

from distutils.core import setup

from distutils.extension import Extension

from Cython.Distutils import build_ext

sources = ["wave2D_u0_loop_c.c", "wave2D_u0_loop_c_cy.pyx"]

module = "wave2D_u0_loop_c_cy"

setup(

name=module,

ext_modules=[

Extension(

module,

sources,

libraries=[], # C libs to link with

)

],

cmdclass={"build_ext": build_ext},

)All we need to specify is the .c file(s) and the .pyx interface file. Cython is automatically run to generate the necessary wrapper code. Files are then compiled and linked to an extension module residing in the file wave2D_u0_loop_c_cy.so. Here is a session with running setup.py and examining the resulting module in Python

Terminal> python setup.py build_ext --inplace

Terminal> python

>>> import wave2D_u0_loop_c_cy as m

>>> dir(m)

['__builtins__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__name__', '__package__',

'__test__', 'advance_cwrap', 'np']The call to the C version of advance can go like this in Python:

import wave2D_u0_loop_c_cy

advance = wave2D_u0_loop_c_cy.advance_cwrap

...

f_a[:,:] = f(xv, yv, t[n])

u = advance(u, u_n, u_nm1, f_a, Cx2, Cy2, dt2)11.27.1 Efficiency

In this example, the C and Fortran code runs at the same speed, and there are no significant differences in the efficiency of the wrapper code. The overhead implied by the wrapper code is negligible as long as there is little numerical work in the advance function, or in other words, that we work with small meshes.

An alternative to using Cython for interfacing C code is to apply f2py. The C code is the same, just the details of specifying how it is to be called from Python differ. The f2py tool requires the call specification to be a Fortran 90 module defined in a .pyf file. This file was automatically generated when we interfaced a Fortran subroutine. With a C function we need to write this module ourselves, or we can use a trick and let f2py generate it for us. The trick consists in writing the signature of the C function with Fortran syntax and place it in a Fortran file, here wave2D_u0_loop_c_f2py_signature.f:

subroutine advance(u, u_1, u_2, f, Cx2, Cy2, dt2, Nx, Ny)

Cf2py intent(c) advance

integer Nx, Ny, N

real*8 u(0:Nx,0:Ny), u_1(0:Nx,0:Ny), u_2(0:Nx,0:Ny)

real*8 f(0:Nx, 0:Ny), Cx2, Cy2, dt2

Cf2py intent(in, out) u

Cf2py intent(c) u, u_1, u_2, f, Cx2, Cy2, dt2, Nx, Ny

return

endNote that we need a special f2py instruction, through a Cf2py comment line, to specify that all the function arguments are C variables. We also need to tell that the function is actually in C: intent(c) advance.

Since f2py is just concerned with the function signature and not the complete contents of the function body, it can easily generate the Fortran 90 module specification based solely on the signature above:

Terminal> f2py -m wave2D_u0_loop_c_f2py \

-h wave2D_u0_loop_c_f2py.pyf --overwrite-signature \

wave2D_u0_loop_c_f2py_signature.fThe compile and build step is as for the Fortran code, except that we list C files instead of Fortran files:

Terminal> f2py -c wave2D_u0_loop_c_f2py.pyf \

--build-dir tmp_build_c \

-DF2PY_REPORT_ON_ARRAY_COPY=1 wave2D_u0_loop_c.cAs when interfacing Fortran code with f2py, we need to print out the doc string to see the exact call syntax from the Python side. This doc string is identical for the C and Fortran versions of advance.

11.28 Migrating loops to C++ via f2py

C++ is a much more versatile language than C or Fortran and has over the last two decades become very popular for numerical computing. Many will therefore prefer to migrate compute-intensive Python code to C++. This is, in principle, easy: just write the desired C++ code and use some tool for interfacing it from Python. A tool like SWIG can interpret the C++ code and generate interfaces for a wide range of languages, including Python, Perl, Ruby, and Java. However, SWIG is a comprehensive tool with a correspondingly steep learning curve. Alternative tools, such as Boost Python, SIP, and Shiboken are similarly comprehensive. Simpler tools include PyBindGen.

A technically much easier way of interfacing C++ code is to drop the possibility to use C++ classes directly from Python, but instead make a C interface to the C++ code. The C interface can be handled by f2py as shown in the example with pure C code. Such a solution means that classes in Python and C++ cannot be mixed and that only primitive data types like numbers, strings, and arrays can be transferred between Python and C++. Actually, this is often a very good solution because it forces the C++ code to work on array data, which usually gives faster code than if fancy data structures with classes are used. The arrays coming from Python, and looking like plain C/C++ arrays, can be efficiently wrapped in more user-friendly C++ array classes in the C++ code, if desired.

11.29 Software Engineering with Devito

The previous sections described traditional approaches to migrating Python loops to compiled languages. Devito provides an alternative paradigm: write the mathematics symbolically in Python, and let the framework generate optimized C code automatically.

11.29.1 The Devito Approach

Instead of manually writing C, Cython, or Fortran code, Devito:

- Accepts symbolic PDE specifications in Python

- Automatically generates optimized C/C++ code

- Compiles and caches the generated code

- Provides OpenMP parallelization and optional GPU support

This eliminates the need for manual low-level coding while achieving competitive performance with hand-tuned implementations.

11.29.2 Project Structure for Devito Applications

A well-organized Devito project follows standard Python package conventions:

my_pde_solver/

+-- src/

| +-- __init__.py

| +-- solvers/

| | +-- __init__.py

| | +-- wave.py # Wave equation solvers

| | +-- diffusion.py # Diffusion equation solvers

| +-- utils/

| +-- __init__.py

| +-- visualization.py # Plotting utilities

| +-- convergence.py # Convergence testing

+-- tests/

| +-- conftest.py # Pytest fixtures

| +-- test_wave.py

| +-- test_diffusion.py

+-- examples/

| +-- run_simulation.py

+-- pyproject.toml

+-- README.md11.29.3 Pytest Fixtures for Devito Testing

Devito’s Grid and Function objects can be reused across tests using pytest fixtures:

# tests/conftest.py

import pytest

import numpy as np

from devito import Grid, TimeFunction, Function

@pytest.fixture

def grid_1d():

"""Create a standard 1D grid for testing."""

return Grid(shape=(101,), extent=(1.0,))

@pytest.fixture

def grid_2d():

"""Create a standard 2D grid for testing."""

return Grid(shape=(101, 101), extent=(1.0, 1.0))

@pytest.fixture

def wave_field(grid_2d):

"""Create a TimeFunction for wave equation testing."""

return TimeFunction(name='u', grid=grid_2d,

time_order=2, space_order=4)

@pytest.fixture

def velocity_model(grid_2d):

"""Create a velocity model with constant value."""

c = Function(name='c', grid=grid_2d)

c.data[:] = 1500.0 # m/s

return cUsage in tests:

# tests/test_wave.py

def test_wave_propagation(grid_2d, wave_field, velocity_model):

"""Test that wave equation solver runs without error."""

from src.solvers.wave import solve_acoustic_wave

result = solve_acoustic_wave(

grid=grid_2d,

u=wave_field,

c=velocity_model,

T=0.1,

)

assert result is not None

assert not np.isnan(result.u.data).any()11.29.4 Convergence Testing Pattern

Verifying numerical schemes against manufactured solutions is essential. Here’s a reusable pattern:

def convergence_test(solver_func, exact_solution, grid_sizes, **solver_kwargs):

"""

Run a convergence test for a Devito solver.

Parameters

----------

solver_func : callable

Solver function that returns a result with .u attribute

exact_solution : callable

Function(x, t) returning exact solution

grid_sizes : list

List of N values to test

**solver_kwargs : dict

Additional arguments passed to solver

Returns

-------

rates : list

Computed convergence rates between successive refinements

"""

import numpy as np

errors = []

dx_values = []

for N in grid_sizes:

result = solver_func(Nx=N, **solver_kwargs)

# Compute error at final time

x = np.linspace(0, result.L, N + 1)

u_exact = exact_solution(x, result.t)

error = np.max(np.abs(result.u - u_exact))

errors.append(error)

dx_values.append(result.L / N)

# Compute convergence rates

rates = []

for i in range(len(errors) - 1):

rate = np.log(errors[i] / errors[i + 1]) / np.log(2)

rates.append(rate)

return rates

# Usage in test

def test_diffusion_convergence():

from src.solvers.diffusion import solve_diffusion

rates = convergence_test(

solver_func=solve_diffusion,

exact_solution=lambda x, t: np.exp(-np.pi**2 * t) * np.sin(np.pi * x),

grid_sizes=[20, 40, 80, 160],

T=0.01,

a=1.0,

)

# Expect second-order convergence

assert all(r > 1.9 for r in rates), f"Convergence rates {rates} < 2"11.29.5 Performance Profiling with Devito

Devito provides built-in profiling through environment variables:

import os

# Enable performance logging

os.environ['DEVITO_LOGGING'] = 'PERF'

# Run your simulation

from src.solvers.wave import solve_acoustic_wave

result = solve_acoustic_wave(...)

# Output will include timing information for each operatorFor more detailed analysis:

from devito import configuration

# Enable detailed profiling

configuration['profiling'] = 'advanced'

# Create and run operator

op = Operator([update_eq])

summary = op.apply(time=nt, dt=dt)

# Access timing information

print(f"Total time: {summary.globals['fdlike'].time:.3f} s")

print(f"GFLOPS: {summary.globals['fdlike'].gflopss:.2f}")11.29.6 Caching and Compilation

Devito caches compiled operators to avoid recompilation:

from devito import configuration

# View cache location

print(configuration['cachedir'])

# Force recompilation (useful during development)

configuration['jit-backdoor'] = TrueFor production runs, ensure the cache is preserved between runs to avoid recompilation overhead.

11.29.7 Result Classes for Solver Output

Using dataclasses provides clean interfaces for solver results:

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

import numpy as np

@dataclass

class SolverResult:

"""Container for solver output."""

u: np.ndarray # Solution at final time

x: np.ndarray # Spatial grid

t: float # Final time

L: float # Domain length

dx: float # Grid spacing

dt: float # Time step used

nsteps: int # Number of time steps

u_history: list = field(default_factory=list) # Optional history

t_history: list = field(default_factory=list) # Time points

def solve_with_result(...):

"""Solver that returns a SolverResult."""

# ... solver code ...

return SolverResult(

u=np.array(u.data[0, :]),

x=x_values,

t=t_final,

L=L,

dx=dx,

dt=dt,

nsteps=nt,

)11.29.8 Comparison with Manual Optimization

The following table compares Devito with manual optimization approaches:

| Approach | Development Time | Performance | Portability | Maintainability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Python | Low | Poor | High | High |

| NumPy vectorized | Medium | Medium | High | Medium |

| Cython | High | Good | Medium | Low |

| Fortran/f2py | High | Excellent | Low | Low |

| C/C++ | Very High | Excellent | Low | Low |

| Devito | Low | Excellent | High | High |

Devito achieves performance comparable to hand-tuned code while maintaining the simplicity and portability of Python. This makes it an excellent choice for scientific computing projects where both productivity and performance matter.